Perspectives on Ukraine and the Russian Invasion - Global ECCO

Perspectives on Ukraine and the Russian Invasion

Roger B. Myerson, University of Chicago. Winner of the 2007 Nobel Prize in Economics.

Dr. Douglas Borer, Department of Defense Analysis at the US Naval Postgraduate School, asked Dr. Myerson some questions about the causes of the Russian war against Ukraine, the role of allies in Ukraine’s defense, and his perspective on how the war might end.

Can you offer a perspective on the root causes of Russia's invasion of Ukraine?

Successful democratic development in Ukraine makes it harder for the President of Russia to rule his country as an autocrat. This basic fact has been the primary cause of Russia's invasion of Ukraine this year.

To prevent the Russian people from seeing successful democracy in a neighboring Slavic country, President Vladimir Putin has always had a fundamental interest in undermining democracy in Ukraine and suppressing Ukraine's political independence. He has attempted to do so for many years by covert political actions and, since 2014, by promoting forces of separatism in Donbas. As these limited actions were proving insufficient to thwart Ukraine's successful development as an independent state, the Kremlin considered more extreme alternatives. In February 2022, Putin launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine because he erroneously believed that it would enable him to quickly establish a Kremlin-controlled puppet regime in Kyiv, which for him would be the ideal solution to his Ukrainian problem.

But we should ask: How could Putin expect the people of Russia to support him in a war that was ultimately aimed at preventing them from seeing the benefits of democracy in a neighboring country? The president of Russia could not openly admit this war aim, and so he has needed to use other pretexts for his war. Thus, the Kremlin has tried to justify the war with lies about the evil nature of Ukraine's popularly elected government and about a potentially existential threat to Russia from NATO expansion into Ukraine. We can certainly understand how the possibility of a foreign military alliance putting hostile forces within a day's drive from the battlefield of Stalingrad could be useful to mobilize Russian popular support for a war to prevent that possibility. Thus, although Russian fears of Ukraine joining NATO may have had nothing to do with Putin's basic reason for attacking Ukraine, such fears have made it easier for him to convince the Russian people to support his war.

Of course, Putin might have attacked Ukraine even if the possibility of its joining NATO had never been suggested. If Putin had been truly confident of a quick and easy triumph over Ukraine in February 2022, then he could have calculated that pride in the victory of Russian forces could induce the popular support he needed. Also, Russians' doubts about the value of fighting a more costly war could be minimized by lies in the Kremlin-controlled Russian media. But we should recognize that Western assertions about Ukraine's long-term possibility of joining NATO gave Putin a truth he could use to build popular support for his war against Ukraine, even while Ukraine's lack of short-term NATO protection encouraged Putin's hopes of a quick and easy victory. It might have been better if the United States had offered stronger assurances for Ukraine's territorial integrity under the 1994 Budapest Memorandum, which could not be construed as an existential threat against Russia because it was negotiated as part of a deal to give Russia a regional nuclear monopoly.[1]

Why did Putin underestimate the strength of Ukrainian resistance against Russia's invasion?

The success of Ukraine's resistance has been based on the great willingness of the Ukrainian people to fight for their country. People can resist a modern military invasion only if they have a will to fight and the weapons to do so, but weapons alone are not enough. The willingness of Western nations to provide military assistance to Ukraine this year also might have surprised Russia's leaders, but that increased willingness was largely a response to the Ukrainian people's demonstrated determination to fight for freedom.

Thus, the deep resolve of people in every part of Ukraine to defend their national independence has been the most important fundamental factor in the war and, indeed, Putin seriously underestimated it. Ukraine's national aspirations have a long history. Ukraine's independence was declared with overwhelming popular approval in 1991 as the Soviet Union collapsed, but Ukrainian independence had also been declared with broad popular support over 70 years earlier, during the Russian Revolution. People in Ukraine have not forgotten that the suppression of their previous independence by Russian revolutionary armies was followed within a dozen years by the murderous Kremlin-imposed Holodomor (deliberate starvation) that decimated Ukraine’s population.

Since 1991, however, there have been times when Kremlin-sponsored politicians in Ukraine have successfully contended for power with wide support from Ukraine’s voters, especially in the country’s eastern regions. In April 2014, a handful of pro-Russian separatists faced almost no resistance to their subversion of local governments in Donetsk and Luhansk, and the memory of these easy Russian victories may have inspired Putin's confidence as he launched his war this year. But now, as we read reports of people throughout Ukraine rallying to defend their country, accepting great personal cost and sacrifice to maintain their freedom from the Kremlin's rule, we should recognize the dramatic growth of patriotic resolve in Ukraine since 2014.

In February 2022, Vladimir Putin did not understand or even recognize this change, even though it could be clearly seen, for example, in the results of Ukraine's 2019 elections, in which Volodomir Zelenskyy was elected president with majorities in both eastern and western Ukraine. Perhaps Putin's spy agencies, having specialized in spreading disinformation, became so accustomed to untruthfulness that they did not feel any need to report unpleasant facts to their boss.

Between April 2014 and February 2022, what could have caused such an increase in the effective strength of the Ukrainian people's resolve to resist invasion?

We must recognize that Putin's own actions may have contributed to this growth of Ukrainian patriotism, as the continual violence of his "frozen conflict" in Donbas turned more people against Russia's aggression. He should have understood that one country's use of force can stimulate contrary political reactions in other nations.

But we should not give Putin all the credit. People's patriotism must ultimately depend on confidence in the ability of their national political system to serve their vital interests, and we should note that such confidence has been increased by many reforms in Ukraine's government since the Maidan Revolution of Dignity in 2014. Among these reforms, I would argue that reforms in local self-government have done the most to increase the willingness of people in Ukraine to fight for their country. I have been concerned with these decentralization reforms for many years, so let me say something more about their significance.[2]

Citizens are willing to risk their lives to defend their country against insurgency or invasion when they see a connection between service to the state and leadership in their own community. But when Russian agents began actions to subvert some eastern regions of Ukraine in 2014, government in Ukraine was highly centralized along the old Soviet model, and local authorities were dependent on the national leadership in the capital. Accordingly, even under national democracy, people in some regions might understand that their local government was controlled by politicians who were elected by voters from other parts of the country. In such regions, even the most prominent local leaders could feel alienated from the state, which had no use for them. Who would then organize their communities to defend the state at need?

Decentralization reforms in 2015 created a new system of local governments throughout Ukraine, establishing about 1,400 territorial communities (hromadas) in the country by 2020. These locally elected community governments were given a significant share of local taxes to provide local public services, which had formerly been the responsibility of nationally appointed district governors. The results have included measurable improvements in local public spending.[3]

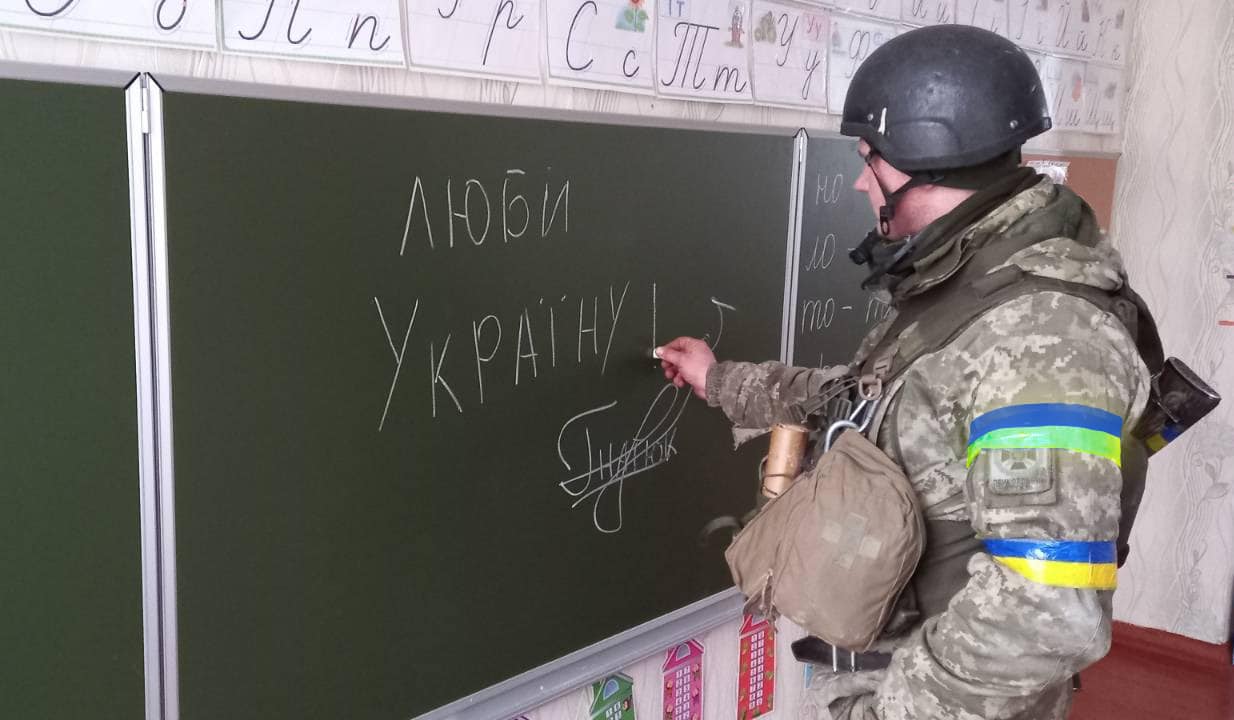

Thus, since 2015, democratic decentralization has ensured the emergence of elected local leaders with real power to organize and maintain local defense. Since the Russian invasion began in February 2022, there have been regular reports of mayors leading their communities in resisting the Russian invaders.[4] As Tymofii Brik and Jennifer Murtazashvili have observed, citizens have rallied not just in support of Zelenskyy in Kyiv, but also to defend their locally elected mayors and community councils.[5]

What can America do to help deter Russian aggression and encourage de-escalation and peace in Ukraine?

A year ago, many of us might have thought that a strong international norm against the use of military force for conquest could have deterred any country from invading another country to seize its territory, as the Russians did in February of this year. If Russia’s armies had the kind of easy triumph that they initially expected when they violated this long-respected norm, then their success would have encouraged other nations to launch similar attacks on their weaker neighbors. Fortunately, strong Ukrainian resistance has forced Putin's government to pay a deep cost for its invasion, and this cost sends a broad deterrent message that such aggression can be dangerous for the aggressor. Thus, our world is a less dangerous place than it might have become after the February 2022 invasion, because people in Ukraine have had the courage and strength to resist the Russian invasion. However, Ukraine's strength has depended not just on its people's resolve, but also on its getting essential military equipment to defend itself against such a formidable invasion. Thus, military assistance to Ukraine has been a vital investment in international security for people in the United States and Europe as well.

It should be clear that the reason the United States has been sending extensive military assistance to Ukraine this year is because Ukraine has been attacked by a massive Russian invasion. This strategic cause-and-effect linkage from their aggression to our support is essential for deterrence. The Russian leadership could be deterred from a further escalation of the conflict if they understood that such escalation would be countered by an even greater increase in our military support for Ukraine.[6]

But Kremlin propagandists have tried to increase Russian popular support for the war by arguing that Russia must conquer Ukraine to prevent Western-equipped forces from invading Russia.[7] This argument exactly reverses the true causal relationship by suggesting that the Russian invasion was a response to American and European military support for Ukraine. To encourage Russians to support greater efforts to conquer Ukraine, Kremlin propagandists have portrayed the West's extensive military assistance to Ukraine as evidence of a Western plan to attack Russia through Ukraine.

This misrepresentation of the true reasons for Western military assistance emphasizes the importance of being extremely clear about the strategic conditions for our actions in deterrence. We do not want Russians reacting to fears that, if their forces were withdrawn from Ukraine, it could then become the forward base for a Western military threat against Russia. It has been difficult to offer credible Western assurances on this point while refusing to rule out the possibility of Ukraine's joining the NATO military alliance sometime in the future.

What hope do you see for peace in Ukraine?

Once wars start, they become very difficult to end. President Putin and his Kremlin colleagues are fearful of losing power if the Russian people recognize the war in Ukraine as a costly mistake, and so they have felt compelled to propagate a myth about an existential threat to Russia from an independent Ukraine that has military ties with the West. But if the Kremlin succeeds in convincing Russians that their own survival depends on making whatever sacrifices are needed to destroy Ukraine, then the people of Ukraine will have reason to fear that any cessation of hostilities would just give Russia time to prepare for a greater and more destructive future invasion of their country. A precedent for such fears can be found in the interlude between the end of the First Chechen War in 1996 and the start of the Second Chechen War in 1999. So, even if there were a cease-fire tomorrow, Ukraine would still need substantial military assistance for protection against Russia's re-armament, and this assistance to Ukraine could still be portrayed as evidence of an existential military threat against Russia to justify greater Russian investments in re-armament. A cease-fire that launches such a dangerous escalating arms race cannot be called peace.

From this dilemma, some have concluded that peace may be impossible without a change of leadership in Russia. But any foreign encouragement for such a change could be taken as further evidence of an intention to subvert Russia's independence.

To escape from this dilemma, we must find a way for Russia, even without changing its leadership, to credibly commit itself to accepting Ukraine as an independent democratic neighbor. Such a commitment could become more credible if more people in Russia understood that the people of Ukraine have been truly united in their determination to defend their nation's independence. If ordinary Russians could see this basic truth, that the strength of Ukrainian national resolve is what halted Russia's invasion this year, then Russians could not be so easily misled into believing that a larger army with more weapons could somehow induce the people of Ukraine to become a different nation.

Thus, we could hope that the first steps toward peace might begin with an opening of communications between Ukraine and Russia, so that people in Russia can learn more about Ukrainians' perspective on this war. Certainly President Zelenskyy could present his case eloquently to the Russian people, if he were able to reach them. But such an opening of communications would require the Kremlin to relax its internal censorship of Russian information about the war, and some observers might question whether there could be any realistic possibility of Putin allowing that while he remains in power. Indeed, I have emphasized here that the fundamental cause of this war can be found in Putin's fears that people might reject his autocratic rule in Russia if they learned about successful democratic government in Ukraine. Nonetheless, urging that Russians should be allowed to hear the truth from Ukraine is fundamentally different from urging Russians to change their government. International diplomatic pressure for the Russian government to relax its censorship of news from Ukraine would be harder for Kremlin propagandists to parry, because this pressure would not imply any lack of respect for the Russian people's sovereignty in selecting their leaders.

This last point deserves more emphasis. Even if we see no realistic possibility of the Kremlin actually agreeing to let the Russian people hear true Ukrainian voices, it could still be helpful to have salient international demands for such a relaxation of Russian censorship as an essential first step toward meaningful peace negotiations. In rejecting these demands, the Russian response would necessarily focus more attention on the basic fact that people in Russia are not getting full information about Ukraine, which should raise doubts about the Kremlin's claims of an existential threat from Ukraine. Such doubts could help to reduce popular support for the Kremlin’s war efforts. Until peace can be achieved, anything that weakens the effectiveness of Kremlin propaganda against Ukraine can potentially save lives.

Ukraine's forceful resistance has taught Russians that their aggression in Ukraine cannot bring them the cheap victories that their leaders dreamed of, only costly defeats. We may hope that, in reaction to these defeats, people in Russia begin to understand that it would be better to start building good relations with a free and independent Ukraine. Indeed, we may observe that the United States has been a better country for having Canada as an independent neighbor, and the people of Great Britain have a better country for having accepted the Republic of Ireland as an independent neighbor. So Russians may someday have a country that is better for accepting a free and independent Ukraine, which can offer an alternative model of democracy in a kindred nation. We know that Vladimir Putin would prefer not to discuss this point, but perhaps he could ultimately be compelled to do so by the need to make peace after the humiliating defeat of his invading forces.

What perspective can you offer on the challenges of rebuilding Ukraine?

The Russian invasion has caused vast destruction in Ukraine, and postwar reconstruction will be expensive. The victory of freedom in Ukraine should offer an example for a better world, but this victory will be incomplete as long as the damages wrought by Russian forces remain unrepaired. Putin's war aim of preventing Ukraine from being a positive example of successful democratic development could yet be achieved, even after the defeat of his military forces, if the devastation of his war leaves a permanent legacy of suffering for Ukraine’s people. Thus, generous offers of reconstruction assistance from the United States and Europe will be appropriate, benefitting the broad global interests of the donors as well as the recipients.

It can certainly be argued that Russians have a moral obligation to pay reparations for the destruction that their forces have caused, but trying to compel Russia to pay a massive reparations debt could be very dangerous. Efforts to extract reparations from Germany after World War I ultimately poisoned postwar German politics, setting the stage for the rise of a militant regime that launched a second world war that was even more costly than the first. This precedent would argue against trying to compel Russia to pay more after the war than the value of Russian foreign assets that have already been seized.

The cost of Ukraine's reconstruction will be a fraction of what the United States and its European allies expect to spend for defense and security over a period of several years. Successful support for postwar reconstruction in Ukraine could become a strong positive precedent for encouraging a more peaceful international order, and so reconstruction assistance may be considered a good investment by the standards that we use to evaluate defense budgets. But the assistance funds must be spent effectively.

A basic lesson from the Marshall Plan for the postwar reconstruction of Europe in 1948 was that foreign reconstruction assistance can be much more effective when it helps to promote reforms that will be fundamental for successful future development.[8] Reforms that have been widely considered vital for Ukraine's future development include strengthening ties with the European Union and increasing the capacity of local governments to serve their communities.

The first of these considerations has motivated a recent report's recommendation that all foreign reconstruction assistance should be coordinated and supervised by an agency of the European Union.[9] That is, even reconstruction assistance from the United States should be channeled through an EU agency, because government officials in Ukraine can benefit from the experience of working with the EU's fiscal regulations and standards, given that closer integration with the EU could be vital for Ukraine's future prosperity.

Reconstruction work must be under the direction of officials of Ukraine's sovereign democratic government. But donors should recognize that the people of Ukraine have been fighting to defend a system of government in 2022 that includes responsible locally elected officials as well as nationally elected officials of the central government. To support and advance the vital growth of local government in Ukraine, a significant share of foreign reconstruction assistance should be set aside for use by local governments. That is, while the largest portion (perhaps two thirds) of foreign assistance should be directed by officials of Ukraine's national government, a significant portion should be budgeted for allocation by local reconstruction boards that consist of locally elected officials. In each district of Ukraine, an official of the European assistance agency could work with the local mayors and other locally elected officials to help them develop and implement a plan for allocating their district's share of the locally directed portion of foreign assistance. In this way, the process of rebuilding the infrastructure of Ukraine can also help to promote the development of local governments' capacity to serve their communities, an effort that is vital for Ukraine's successful democratic development.

Ukraine's success in resisting a massive Russian invasion in 2022 has been based on its people's confidence in the ability of an independent Ukraine to provide a better future for them, and reforms to establish responsible local governments have contributed to this confidence. After the war, the international community should generously support the development of an independent democratic Ukraine that can build peaceful and mutually beneficial relations with all its neighbors. But above all, the postwar reconstruction of Ukraine should aim to fulfill its people's hopes for a better future, for which they have given so much.

About the Author

Roger B. Myerson is the David L. Pearson Distinguished Service Professor of Global Conflict Studies in the Harris School of Public Policy at the University of Chicago. He has used game-theoretic analysis to study political systems, and has published many articles on comparative electoral systems, strategic deterrence, moral hazard and leadership in the foundations of the state, and the vital importance of local democracy in state building. He first visited Ukraine in 2014 to participate in discussions about decentralization reforms there, and he currently serves as chair of the international advisory board for the Kyiv School of Economics. In 2007, he was awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for his contributions to mechanism design theory, which analyzes rules for coordinating economic agents efficiently when they have different information and difficulty trusting each other.

Copyright 2022, Roger B. Myerson. The US federal government is granted for itself and others acting on its behalf in perpetuity a paid-up, nonexclusive, irrevocable worldwide license in this work to reproduce, prepare derivative works, distribute copies to the public, and perform publicly and display publicly, by or on behalf of the US federal government. All other rights are reserved by the copyright owner(s). Foreign copyrights may apply.

How to cite this article: Roger B. Myerson, “Perspectives on Ukraine and the Russian Invasion,” ECCO Insights, 7 January 2023: https://nps.edu/web/ecco/global-ecco-insights

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________

1. The Budapest Memorandum on Security Assurances, which provided for the removal of Soviet-era nuclear weapons from Ukraine after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, was signed by Ukraine, the Russian Federation, the United States, and the United Kingdom in 1994. For more on this argument, see Roger Myerson, “President of Ukraine Should Talk About Guarantees Under the Budapest Memorandum, Not About NATO Extension,” Vox Ukraine, 18 February 2022: https://voxukraine.org/en/president-of-ukraine-should-talk-about-guarantees-under-the-budapest-memorandum-not-about-nato-extension/. See also John Herbst and Roger Myerson, “Three Ways America Should Respond to the Ukraine Crisis,” Huffington Post, last modified 3 February 2015: https://www.huffpost.com/entry/america-ukraine-response_b_6270380

2. See Tymofiy Mylovanov, Roger Myerson, and Gerard Roland, “Ukraine Needs Decentralization to Develop Future Democratic Leaders,” Vox Ukraine, 17 August 2015: https://voxukraine.org/en/ukraine-needs-decentralization-to-develop-future-democratic-leaders/

3. See Anna Harus and Oleh Nivyevskyi, “In Unity There is Strength: The Effect of the Decentralization Reform on Local Budgets in Ukraine,” Vox Ukraine, 6 Aug 2020: https://voxukraine.org/en/in-unity-there-is-strength-the-effect-of-the-decentralization-reform-on-local-budgets-in-ukraine/

4. For example, see Yuras Karmanau, “Russians Try to Subdue Ukrainian Towns By Seizing Mayors,” Associated Press, 3 November 2022: https://apnews.com/article/e4e8d5a847aff39c78871c7ab1cb9c10

5. Tymofii Brik and Jennifer Brick Murtazashvili, “The Source of Ukraine’s Resilience: How Decentralized Governance Brought the Country Together,” Foreign Affairs, 28 June 2022: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/ukraine/2022-06-28/source-ukraines-resilience

6. See also Roger Myerson, “Problems of Credible Strategic Conditionality in Deterrence” (working paper, University of Chicago, 2018): https://home.uchicago.edu/~rmyerson/research/conditionality.pdf

7. For examples of such Kremlin propaganda, see Julia Davis on Twitter @JuliaDavisNews: https://twitter.com/JuliaDavisNews

8. See Harry Bayard Price, The Marshall Plan and Its Meaning (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1955); and J. Bradford De Long and Barry Eichengreen, “The Marshall Plan: History's Most Successful Structural Adjustment Program” (working paper 3899, National Bureau of Economic Research, 1991): http://www.nber.org/papers/w3899

9. Torbjörn Becker, Barry Eichengreen, Yuriy Gorodnichenko, Sergei Guriev, Simon Johnson, Tymofiy Mylovanov, Kenneth Rogoff, and Beatrice Weder di Mauro, “A Blueprint for the Rconstruction of Ukraine,” Centre for Economic Policy Research, 7 April 2022: https://cepr.org/publications/books-and-reports/blueprint-reconstruction-ukraine